- Home

- Pete Salgado

Her Name Was Dolores Page 5

Her Name Was Dolores Read online

Page 5

Gabo finally agreed, calling the producer to make sure everything was set up right for Jenni and explaining that he had gotten “held up” and would arrive later. She grabbed her stuff and took off to Telemundo, while he stayed behind to face the remnants of their latest fight, not knowing how Juan would react and what he would have to do to take control of the situation.

“Pinche vieja, she’s loca!” said Juan as soon as Jenni was out of earshot. “She got angry about another woman, but I told her over and over again that nothing had happened, that I hadn’t done anything.” Juan went on to tell him they’d thrown things at each other, a hair straightener, whatever they could get their hands on—something that was common in their fights. Things always flew through the air when their arguments got heated. Gabo, flabbergasted by the whole situation, was finally able to reason with Juan, reminding him that this was the first day of a week-long promo trip that ended with them flying straight to one of Jenni’s Friday night gigs. So Juan calmed down, and promised he wouldn’t do anything to her stuff. Crisis averted! One down, many more to go.

Life on the road with Jenni was always entertaining, to say the least. Gabo has fond memories of those early days, where they would all pile into a conversion van with seats that turned into beds, and hit the highway, touring every weekend and many weekdays, playing the circuits, trying to make Jenni Rivera a household name. Juan would drive, she’d sit next to him, and Gabo would sit in the back with the musicians. Jen had put together a four-piece Norteño band that became her musical entourage.

Yes, she recorded banda-style, with many more musicians, but early on it was more cost-effective for her to perform with a smaller Norteño band. This was a big step for her; it meant she was no longer working with local musicians in each town, but instead rocking out with a self-curated crew of guys there to back La Diva’s act. Two of them were her friends: El Gordo, the music director, and Gil, the band leader. They were really talented and they knew Jen like the back of their hand. She traveled, toured, lived, and created with these men. The other two musicians rotated because in the beginning there weren’t enough steady gigs to keep them all on full-time.

El Gordo and Gil stayed on with Jenni until around the Parrandera, rebelde y atrevida album released in 2005. After that we went full banda. To Gabo’s credit, he was the one who told her: “If you want to charge more money, you have to get your own banda. The only way you’re going to get more money is performing with banda.” And it was hard. She saved money with the Norteño band, so it was tough to decide to go out on a limb and increase her overhead, but it paid off. From then on, she’d still use el Gordo when she was recording. He’d come around to guide her when she was laying down the vocal tracks. Yet, by then, Jen didn’t really need much guidance in that area. I think she kept accepting his help to keep him in the loop in her career. Jenni was such a loyal person that if you were loyal to her, she found a way for you to stay on board. She never forgot the people who were there for her when she was a nobody. That was Jenni for you.

In any case, back on the road, Jen was usually the lone woman in that crew, but she knew how to handle herself. From the start, Jen always made it clear she was one of the guys. She grew up in a house with four brothers, her little sister came later, so getting down with the fellas was nothing new to her, even now when she was in the thick of it, getting hot-boxed in the tour van by a gaggle of burly musicians; the kind of dudes who always had a beer in one hand and a joint in the other. It was an experience of growth for her, not because she was the only woman, but because she was the leader. It wasn’t about being a woman; it was about being the boss.

Later, Jen hired Jessie, the bass player’s wife, as her assistant, and she’d also join them on the road, selling merchandise and photos to the growing number of fans. As Gabo recalls, “We were all pulling our weight to help her make it. I remember we’d make pit stops at an ampm or a 7-Eleven before hitting the freeway to load up the van with food for the drive, which usually was around four to five hours long between stops. We’d get lots of junk food, Doritos, Fritos, Gatorade, peanuts, water too. A typical weekend meant driving to Bakersfield on Friday, San José on Saturday, and Fresno or Stockton on Sunday, then back to L.A. Later, once we started expanding our territory and getting out-of-state gigs, we’d drive, in that same van, to Arizona, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.”

Juan was only around for the beginning of these road trips—their relationship had come to an end by the time Jen started touring more frequently. She knew that being married to her so-called manager would be difficult, especially to a good-looking man who was in the audience doing his thing, getting attention from the crowd, while she was on stage seeing what she felt was his flirtatiousness in all its glory. And, given their history, her jealousy was far from unfounded, and incredibly difficult to manage while performing.

One time, Gabo recalls, they had traveled to San Antonio, Texas, for a gig, and her jealousy suddenly spun out of control when he least expected it. Jenni was on stage performing, doing a fantastic job as always, the crowd cheering her on and loving every minute of it, when Juan turned to Gabo and said, “I’ll be right back. I’m going to the bathroom.” He walked off, and along the way a young woman stopped him to ask him something about Jenni, at least that was Juan’s version of the story. Gabo didn’t even realize what was happening until seconds later, when he heard Jenni say over the mic, “Te estoy viendo cabrón, te estoy viendo …” (I see you, cabrón, I see you.) Some people in the audience started looking over their shoulders trying to figure out what the hell she was talking about because it had nothing to do with the song she was singing; it came totally out of left field. Before Gabo had the chance to even react, he heard her say, “Ahorita vengo. Espérenme.” (Hold on, I’ll be right back.) And she stopped singing midway through a tune, set the mic down, and left the stage while the band continued to play, glancing at one another and wondering what Jenni was up to now.

She stomped down those stairs, flew by Gabo, and headed straight to Juan, who was still chatting with this woman, clueless as to what had just happened behind him. And, man, did she go in on him, “What do you think you’re doing, pendejo? Do you think I’m blind? Do you think for one second that I can’t see who you’re looking at? I’ve got eyes everywhere! Just wait until we get back to the hotel! All hell’s gonna break loose!” Juan was taken so aback he was speechless. Gabo remembers, “As soon as I realized what was happening, I ran after Jenni. She had left the stage midway through a song and had to go back and finish it! It was only a matter of minutes, and as I reached her, she was already wrapping it up and heading back to her performance, but I never knew how those situations were going to unfold and how long they could take.” Thankfully, after she gave Juan a piece of her mind, she whirled around, got back on stage, finished the damn song, and continued her show as if nothing had happened. “I really don’t think Juan would be so shameless as to do something like that right under Jenni’s nose,” says Gabo, “but when there are infidelities and jealousy, all bets are off.”

When Jenni left Juan, she hired a driver who took Juan’s place on the tours and helped her with whatever she needed. Things went smoother for Gabo after that because this guy had taken Jenni’s husband’s role on the road, but she didn’t sleep with him, so there was no damn drama to be had. That’s when Jenni and Gabo really began to bond and forge their friendship. During those long journeys, they began to open up to each other, beyond work-related subjects, getting into more personal stuff, until eventually they became as close as siblings. When work was done for the day or night, they’d all share some beers or a few tequilas and tell jokes, rolling over with laughter. Then Jenni’s smile would suddenly morph into a weeping willow, and she’d wail out, “I miss my husband!” then add between sobs, “I miss my kids!” Gabo, now used to these sudden outbursts of emotion, would respond, “Relax, mija, don’t worry, you’ll get to see them in about a day.” Jen was hoping she could fix things with Juan, but i

t was too late. Too much water under the bridge. Until one day she finally said, “I can’t take it anymore,” and it was over for good. That’s around the same time she started pouring her emotions into her performances, shedding tears on stage, overwhelmed by the pain caused by the end of her second marriage and the time she had to be away from her children.

Jen was always incredibly open and clear with her children about what she was doing and why she had to leave them to go on the road. Although she sheltered them, she was always straight forward and honest with them. They knew what mama was doing. They understood that when she wasn’t with them, it was because she was out working for them, for their needs, to give them better lives, so they never lacked anything … but that didn’t mean it hurt her any less. It was a huge sacrifice for her, the biggest one she had to make; it really killed her inside, but it was all for them, for her princesses and princes, for the real loves of her life.

Before Jenni passed, during one of our many conversations on this topic, she expressed that all she really wanted was to be close to her children, to not miss any more birthdays, to be there for their school events, to be nearby when they needed her the most. And I said, “Look at Shakira. She was incredibly successful, even managed to cross over into the American market, but once she got married and had children, she put her career on hold to be with her family.” I pointed out to Jen that she had done the opposite. She had started off as a mom and then decided to work hard on her career for her kids. It was most definitely a motherly act, just not the traditional stay-at-home kind, and it had worked. She’d made it work. Even when she was traveling, she always did everything in her power to loop in her children, to call them between gigs and check up on them, to incorporate them as much as possible into her busy life. She was a mom who had to go on the road to make a living, but a mama bear nonetheless.

While she struggled with these separations, Gabo struggled to get her gigs, especially when he first joined her team. “It was really hard at the beginning,” he recalls. “I’d try to sell her to the concert promoters I knew, but they just wanted Lupillo. They thought hiring Jenni was a waste of time and money. And I’d insist that she had her Malandrinas, her army of women who faithfully followed her everywhere. They were still hesitant, so I’d say, ‘Listen, give her a shot, and if it turns out you’re not happy, just don’t book her again.’ Slowly, I was able to convince them to give us a shot—having a good relationship with them from before also helped.” That’s how Gabo managed to pull it off.

The promoters agreed to book her for a very low initial fee that was tied to the crowd she drew. The more people she brought, the better paid the gig would be. The ladder ahead to stardom was a long one, but they had at least gone up the first few steps. However, absolutely nothing happened overnight. It took a lot of hard work, rejection, convincing those who were skeptical, but in the end, we did it. Think about it: if it’s hard for men to break into this music scene, imagine how hard it is for a woman? As Gabo said in one of our conversations, “The problem with female artists in Mexican Regional music is that usually they look great on the venue’s billboard, but they don’t sell tickets. Why? Because women fans are very, very jealous. They don’t want to take their husbands to see a woman who’s hotter than them. They may listen to their songs, but they sure as hell don’t flock to their concerts. Now with Jenni it was different. She didn’t look like a model, she looked like them, and she was singing to and for them with her characteristic spunk and charisma. She wasn’t a threat, she was their best gal pal, she was their ally, she was their champion. Jenni could sell the hell out of those tickets, and I knew it. Now I just had to convince the promoters to give her a shot.”

Eventually, she started getting more and more airplay, and suddenly it was the promoters who were knocking on our door asking her to please play at their venues. Women didn’t really have a voice in the Mexican Regional music genre until Jen came along. And with time, and hard work, her growing number of fans helped Jen begin to see herself in this new light. With each show, she noticed the huge impact she had on her audience, and this only pushed her to give them more and more of herself. She’d often say, “I have to do my best in every show, no matter how large or small, as if it were the first, as if it were the last.” And that’s exactly what she did. No matter what stage she was on, she always gave it her all, even if that meant breaking down and weeping onstage because the line between the expression of her art and her personal life was a fine one. The more she performed, the more people wanted to know the details of her life story, and right out of the gate, she was an open book.

Chapter 4

Love and Music

Every time Jenni hit the stage there was a transformation. As soon as she grabbed the mic, she tuned out reality and tuned in a different world. This was a world where she was in charge, where she could express her musical gift openly; it was also a shelter from her problems, a place where all she felt was the love of her fans and the exhilaration of her performance. The stage served as her respite, and in those few hours up there she could breathe and laugh and let go of whatever might have been weighing her down. There were no responsibilities; it was a place to express her emotions to the point of tears and laughter and just have a good old time. No one had the power to interrupt her during those moments on stage. However, as soon as she stepped out of the limelight, she walked right back into her reality, which was centered around her divorce from Juan López when I joined her team.

Jenni’s Second Marriage to Juan López Ends in Divorce

Jenni filed for divorce in April 2003, right around the time I started working with her, so this was my first Jenni Rivera media wrangle. The divorce in itself was difficult because her two youngest children, Jenicka and Johnny, loved their dad, and she didn’t want her problems with him to affect the relationship they had with Juan. It was also difficult on Jenni because she had worked so hard trying to make it work for her kids, for herself. Juan was a good-looking man and a bad ass who didn’t take shit from anyone, the kind of man Jen imagined would keep her safe. Yet, as the years went by, things took a turn for the worse in their relationship, and they were going nowhere fast. Their fights escalated, as did Jen’s frustration for feeling that she was the man of the house, the provider, the ambitious one, the one who rolled up her sleeves and did whatever it took to get the job done. Yes, Juan was her manager, but it was difficult; there wasn’t a clear line between what he made and what she brought home, so that became another constant struggle. And then there were his infidelities, which only made the situation worse. Jen’s jealousy skyrocketed after discovering his first affairs, and she was never capable of fully trusting him again. So while her music career was finally beginning to go somewhere, her marriage was tanking, and all roads led to their inevitable divorce.

Up until here, it sounds like the familiar divorce story we’ve all heard time and again, infidelities, irreconcilable differences, and so on, but then Juan threw in a curve ball that sent Jen reeling. Juan not only was requesting alimony, he wanted to include a sunset clause in his spousal payment so that he would continue receiving a percentage of her earnings throughout the duration of her career. How could this strong macho man suddenly turn around and ask for alimony? This was unheard of among the Mexicanos we knew, but what really set her off was that he was also suddenly claiming ownership of her career. She was shocked and furious, “I can’t believe the son of a bitch has the balls to even ask me for this,” she said to me. “I’m raising the kids, taking care of everything, I stood by him when he went to jail, I married him so he wouldn’t get deported, I had to deal with his infidelities, and now he has the audacity to claim to have ownership of my career?”

Yes, that’s exactly what he was doing. He believed he was owed a lifelong residual from her because he claimed he had initiated and invested in her career. Boy did that light Jenni on fire. No one made her. She made herself. But he had been afforded a certain lifestyle under Jenni’s wing, and now he

felt he was entitled to keep it. He’d gotten used to living comfortably and being pampered, and he wasn’t about to give all that up without battling it out. But he picked a fight with the wrong woman. Jen had a huge issue with people when they suddenly felt a sense of entitlement. She’d earned every penny in her name through blood, sweat, and tears, and she believed everyone around her—employees, friends, and family—should do the same. You get out there, give it your all, and earn your spot on a team in this world. It’s not simply handed over to you. Jen never received any handouts, and she’d be damned if she was about to give one to this guy.

The divorce, which Jen hoped would be a quiet one that would resolve within a year, turned into a long and arduous public battle that lasted three years and was finally settled in June 2006. My initial approach was to control what went public, to carefully decide what we shared with the media, but Jen had another idea in mind: she wanted to use the media to give light to her battle, something that I believed to be very risky. The media is like a snake. You have to be very careful with how you handle it because it could just as easily swing around and bite and poison you when you least expect it. That’s pretty much how I put it to Jen when we were going back and forth on how public to go with this divorce, but Yanalté, her then publicist, who thrived on garnering attention for her regardless of whether it was positive or negative press, didn’t agree with me and continued to fuel Jenni’s fire, one that was easy to feed.

Jen was a sensitive soul who didn’t really think things through when she was hurt, but rather immediately reacted with her emotions. She’d raise her guard and slide into attack mode, throwing punches left and right until she knocked down the culprit. If something didn’t sit well with Jen, she wouldn’t take her time to figure out the best way to handle the situation. She’d pick up a phone, go to a TV show, open up Twitter, and openly confront whoever had rubbed her the wrong way, so my reasonable approach on how to handle the media quickly went out the window this first time around. It wasn’t until later in life that she learned how to first process information and then react accordingly, but it was never in her nature. It went against her very essence, and it always required a huge effort on her behalf not to pounce like a tiger when feeling threatened.

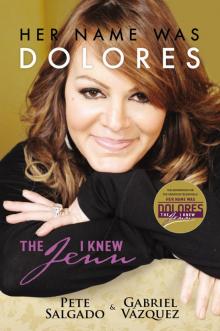

Her Name Was Dolores

Her Name Was Dolores